We Don’t Really Work For A Living.

There’s something interesting going on at Catalyst. It seems like no one really works here. That admittedly sounds like an odd thing to say since volumes of work gets done around here every day, but I think it’s true and here’s why. During a recent meeting, Dennis Turner, one of the company co-founders, said something that stood out: “Most of what I needed to know about plastics, I didn’t learn in college.” People chuckled and the conversation went on without much explanation. I knew I was going to catch up with Dennis later to see what he meant by that.

The facts are that this man helps to run a product development company, which includes intricate and technical processes related to the successful design and engineering of plastic injection-molded components. Not to mention, he has helped clients assign more than 50 patents on products that require manufacturing expertise in plastics. Color me impressed! Surely, he was trained about these things in college. So what did he mean by that?

I did end up having a longer talk with Dennis about what he meant and I think it’s worth a few minutes to share some of that conversation with you.

Q: Tell me more of the meaning behind your comment in the meeting.

A: “College teaches you how to learn, but you gain the most experience from getting out there and doing it. There are college graduates who don’t know the first thing about how to actually make something in the real world. I was able to learn a lot about plastics before I was even accepted into design school and some of the questions I had weren’t even answered by professors, they were very general … very 30-thousand foot view.”

Q: If the bulk of your experience didn’t come from college courses, where did it come from?

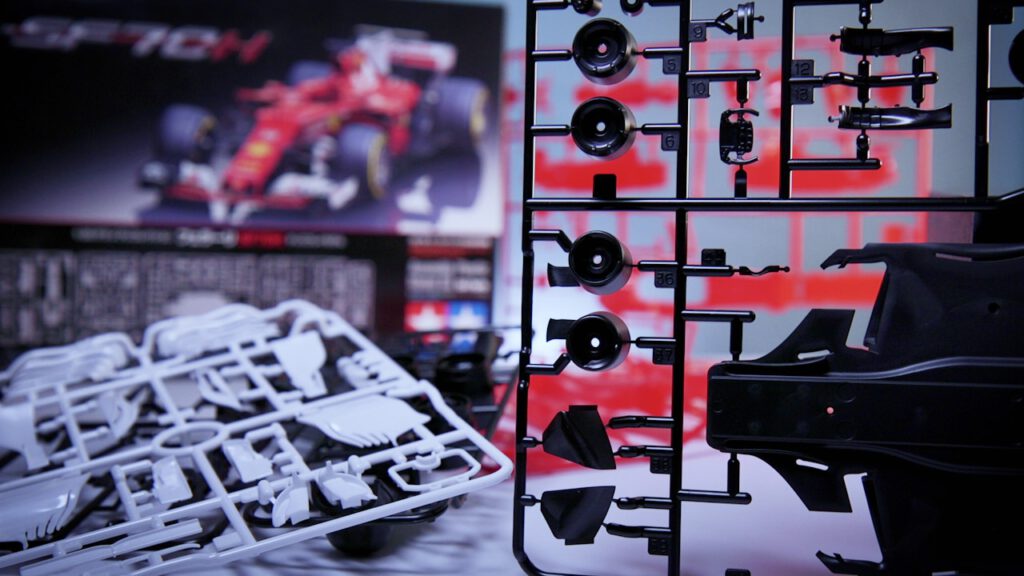

A: “Let’s go way back … As a child I was interested in how things were made, how they were built. That kind of drove me to build plastic model kits because they taught me how cool things like jets and cars were built. I couldn’t help but notice that the plastic pieces were on runners which were attached to a sprue and the pieces were colored, polished or textured. Some models had amazing craftsmanship and fine details that required very little finishing. Other sets seemed sloppy and you could tell the molds were subpar. I learned how different plastics would react to heat and chemicals. I’d cast things in silicone, I’d cast parts in wax … RTV too. Of course, one of my favorites was the Creepy Crawlers set with molds and thermoset plastic.

At a very early age, I’d take something like an old alarm clock apart because I wanted to see how it worked. I couldn’t necessarily put it back together at that point. But it really starts to click when you realize how to reassemble things and even fix stuff that had stopped working. All of this was done before I was the age of 13 or 14. It was all building up experience about materials and processes that I didn’t even realize that I was learning at the time.”

Q: So you were getting the most knowledge from your life experiences, when did it really click that this should be your career path?

A: “Really the breakthrough for me was when I was dating my wife. One of her best friend’s dad was Charlie Cummings, an accomplished engineer at Kenner Toys. He took me on a tour where they were making Star Wars toys at the time. When I saw the industrial design there, I got pretty excited. We got special permission to see those toys being molded and assembled … the whole operation blew me away.

The molds were gigantic. They were making things that had many different components … huge machines that were holding the molds together. They were shooting parts in beryllium copper molds for super high detail. I ended up doing an extra-credit research project on the process and presented it to my design class. It really talked about the process, what knock-out pins do, draft angles, where the gates go, what hot runners are, and of course melt temperatures. It really showed what injection molding looks like in the real world. At the time, my professor had never even seen an assembly line like that.”

Dennis has simply been pursuing his passion since he was a kid.

He got a leg up on other design students in college because he had already gained building experience and showed he has what it takes to make a concept succeed in product development. Career benefits were cemented in design school because he had taken the time to pursue his interests. Going the extra mile doesn’t seem difficult when you love what you do, right? That talk with Dennis brought to mind the famous Mark Twain quote:

“Find a job you enjoy doing, and you will never have to work a day in your life.”

Jack Lawson and Dennis Turner started Catalyst out of a passion for the creation process. And if you look around at the people working at this company, you see the meaning of that Twain quote at play. Catalyst has a way of finding people who are truly passionate about what they do.

The industrial designers really dive into capturing a new vision of how to create innovative products that people want. They pour over form, textures, colors and design aspects like it’s an addictive hobby. Each project benefits from engineers who were literally born to maximize every efficiency in those designs. It’s obvious the techs out on the shop floor love crafting things with their hands. Each phase in product development at Catalyst is a dance between science and art which shows through in the designs, prototypes and final product. So it’s no surprise that many of our new projects are repeat business with existing clients or customer referrals.

“The Catalyst Difference.”

If fate had played out differently and Dennis hadn’t started Catalyst with Jack, they’d both probably have to go to work every day. But, they don’t go to work … actually none of us do. We get to come here instead. That’s what I believe Dennis was getting at when we were in that meeting. Time and again I’ve heard our business model described as an industrial design firm with a really kickin’ prototype lab as our playground. I think that statement sums it up pretty well.